The Curb-Cut Effect and Accessibility at Events

Source : PCMA

Author: Barbara Palmer

When Meryl Evans is deciding whether to watch a webinar or participate in a digital event, the first thing she considers is not the speakers or subject matter, she told an audience at Convening Leaders 2022 in January. Evans, who was born profoundly deaf, said she looks to see whether the event is captioned.

“If I look for captions first and see none, then I move on and won’t know what I’m missing — there are plenty of captioned webinars out there,” she said during the session, “Demystifying Accessibility: How to Make Sure Your Events and Experiences are Inclusive and Inviting.” Don’t make people register before they can see accessibility services like captioning, Evans advised — include that information out in front on the landing page. “People want to know this before signing up.”

Those are the kinds of insights available to planners who directly ask participants and speakers who have disabilities about the kinds of services that they need and want. Meeting organizers often make blanket assumptions about the accessibility services that participants, including speakers, will need, Evans said. One of the most common mistaken assumptions is that all deaf people know sign language, she said. Evans is one of many who do not.

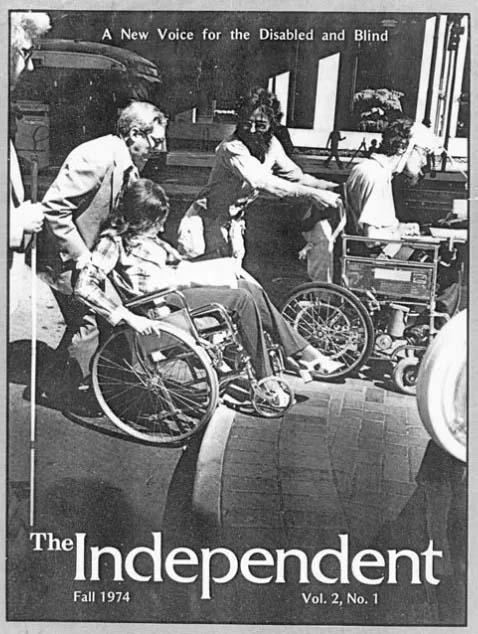

Pressed by disabled activists, in 1972, the city of Berkeley, California, installed its first official curb cut. It became “the slab of concrete heard around the world” — hundreds of thousands of curb cuts have since been made in the U.S.

“Deaf people don’t fall into neat little buckets. Not everyone can read lips or sign. Not everyone wears a hearing device. Deaf and hard of hearing folks are all different.”

Beki Winchel, PCMA’s former learning content and research developer, learned the challenges of being a lipreader firsthand when she worked with Evans in the lead-up to and on site at Convening Leaders. Evans shared that as an audience member she misses portions of presentations if the speaker moves around on stage and their face is obscured — something Winchel had not considered before Evans pointed it out.

Face masks worn to help prevent the spread of COVID present additional barriers to lipreaders. “Because Las Vegas’s mask mandate was in effect for Convening Leaders,” Winchel said, “a member of the PCMA team met Meryl and assisted her through registration, using text messages to communicate along the way.” During the Q&A portion of Evans’ session, attendees typed their questions into the JUNO virtual event app, “but a back-up moderator was prepared to take questions and repeat them,” Winchel said, “unmasked, and socially distanced near the stage.” (Read Winchel’s account of the experience, Learning Firsthand How to Make Events Accessible.)

For Everyone’s Benefit

During her presentation, Evans, a frequent speaker and certified accessibility and diversity trainer, also made a case for what she called the “business benefit” to the entire audience — not just those with current disabilities — of creating accessible and inclusive events.

People with disabilities are the largest minority group in the world, Evans said, “and it’s one that anyone can join anytime.” Alongside those who communicate their need for services, “there are many invisible disabilities” that go unreported because people fear they will lose opportunities if they disclose them, Evans said.

But even beyond those groups, accessibility and inclusion efforts benefit far more people, Evans said. She cited the “curb-cut effect,” which is the cascade of benefits that came to many more groups in addition to wheelchair users after disability advocates succeeded in making the cut — ramps that grade down from sidewalks to the adjoining street — mandatory in many places.

Download Cornell University’s accessible meeting and event checklist.

Curb cuts ended up helping many people — parents pushing strollers, travelers pulling luggage, skateboarders, bicyclists, and workers carrying heavy loads, Evans said. “They aren’t just found on street corners. You can find them at airports, grocery stores, office buildings, and many other places.”

Adding captioning to live-cast and recorded events is a great example of the curb-cut effect in action, Evans said. Closed captioning debuted in the 1970s to serve deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals — but now “80 percent of the people who use captions are not deaf or hard of hearing,” she said.

When possible, choose quality caption providers that offer participants a better experience, Evans said — for example, the option to customize their size and font. Evans reinforced that “auto-captioning will only go so far,” Winchel said. “Often it makes mistakes with names and will misinterpret phrases, so repeating and understanding context is necessary.”

People often ask Evans is if they should provide captions or transcripts — she recommends both. Unlike captions, transcripts are accessible to people who use Braille and screen readers, she said. “And captions move too fast for some people.”

There’s a “curb-cut effect” to making transcripts available to participants, Evans added. Transcripts allow all users to search a video or podcast for specific points, and also makes it easy to reuse content for articles and other formats, she said.

Considering accessibility and inclusivity from the outset in all aspects of events make things easier for both organizers and participants, Evans advised. Like discovering a missing ingredient to a batch of cookies, “you can’t add it after baking. The only way to fix it is to start over,” she said. “It costs more to fix accessibility problems than to bake accessibility in from the start.”